In my experience, good landscape design is underpinned by a number oflandscape design principles.In today's post I want to explore 10 of the most important elements and principles landscape designers use to "ground" their ideas within the site they are working in.

It's easier to think of ideas ‘in the abstract' – that is, floating in the ether, not connected to anything – I talk more about Theory in this post.Introducing reality makes it difficult to make these ideas ‘work' because you are adding constraints that prevent you doing what you want, or planned, to do.

This is where landscape design principles come in.

Landscape design principles help designers apply theoretical ideas or concepts to a real world scenario.Through the landscape design process, the designer explores different ideas, or different versions of a similar idea, to see what works best in this situation.

Part of this testing or iteration involves changing aspects of the design – layouts, dimensions of spaces and objects, and materials.These aspects areformedby a combination of landscape design principles, such as:

- Line

- Colour

- Texture

- Proportion

- Contrast

- Solid vs Void

- Unity

- Repetition & Rhythm

- Hierarchy

- Symmetry/Asymmetry

While simple, these principles – sometimes referred to as elements – are what thelandscape designer utilisesfirstto help sketch, explore and test their designs.Every landscape or garden ever designed was developed using some combination of these principles.

华体会ufcLet's look at each one in more detail, and how that landscape design principle informs garden design.

1.How Line In Your Garden Defines Your Style

Line is a core element within landscape design.华体会平台赞助It falls under ‘Form' in landscape design theory – things concerned predominantly with thelookandaestheticof an object or space.

The type of lines used in a design also strongly hint at thegarden style.Straight, bold lines suggest something formaland/or modern.Curved lines hint at something more ‘natural' or informal.

Line impacts design not just at the macro level, but right down to the smallest details.It often serves as atransitionbetween things.From one object to another.One material to another.One space to another.

These transitions at the smallest levels mirror the overall garden style at the site or yard level.Straight and bold lines between areas equalstrong and clear transitions between materials and objects.These lineslead the eye, holding anddirecting attention– something you want in a formal or modern garden.

Curved lines favour a more natural design withsofter, blurred transitions between materials and objects.This blurring of edges leads to alack of direction for the eye.Designers often contrast this lack of outline with a focal point that is bold and sharp – a feature sculpture or tree that ‘pops' from within a more natural, amorphous, hazy bed.

This idea leads neatly into the tip that lines aren't purely about layout.Vertical lineswithin a design can have a huge impact.As noted above, they can act as afocal point– rising out of the landscape to draw the eye.You canadd depth to a space by having multiple thinner, upright elements.

The ‘weight' of lines is also important – again, it links back to being bold or fuzzy, and how those borders work.Sometimes you can have the same combination of materials and just order them differently, or make some visible and others not – leading to very different results.

One thing to note is that in many cases, the absence of line – of carving up space in some way – can helpgroundus the most.Think of standing in a forest, surrounded by trees, with noclear focal pointor change in the view around you.This lack of transition from one thing to the next – with no dividing line – can be soothing and healing.

2.Tips On Using Colour In Your Landscape Design

Colour is another core element within landscape design.Again, it falls under ‘form' – the look and aesthetic of an object, space or overall design.

If you're new to designing, it can be helpful to determine asmaller colour paletteyou want to work with in the beginning.Take the different ideas and inspiration you like and try to create a list of approximate colours you want to work.

Many beginners don't realise havingmore constraints– more thingslimiting you– is actually helpful.If you have aspecific set of coloursyou want to include across your design, you reduce the number of options available to you – across plants, materials and combinations.This restriction allows you to play with other parts of your design – yourlayout, dimensions, spaces and more.

Back to colour – there is quite a background relating tocolour theoryin many design disciplines.This articlegoes into good detail about how different combinations work together.

A basic summary to keep in mind iscool colours recede in the landscape.This is the opposite to indoors, where a white wall is the common background.In the garden (indeed, in nature)black and darker coloursare what fall back, away from your eye.This can make a space feellarger.

This meanswarm colours come towards you, making spaces feelsmaller– perfect if you want a more intimate, cosy space.Warm colours also work well as feature or focal points –poppingfrom a cooler background.

One last thing to think about when it comes to colour, is to consider, as always,howyou will use the different spaces in your garden.

What time ofday,seasonandyearwill you want to‘view' or use an area?Sunlight can change how we perceive colour – Summer makes colours moreintense, while Wintersubduesthings more.

A good idea as you design and flesh out your layout is to create acolour planthat you overlay on top.Think about when you will be inside looking out, or from one part of the garden looking towards another.Whatcolours do you want to see, andwhenwill you be viewing them?

You don't need to stick to a specific set of colours either.Consider using tonal variants of the main ones –shadesof them, pastels etc.– to build a more layered colour palette.

If you'd like to learn more about landscape design in general, check out my6 Step Beginner's Guide.If you'd like something more in-depth – try my ebooks the Landscape Design 101 Guide or华体会ufcThe Garden Design Process.

3.Designing Your Garden With Texture In Mind

Texture is how a surfacefeels.It applies toplants, materials and the overall ‘effect‘ of a particular view– whether it appearshardorsoftfrom a distance.This ‘effect' is usually drawn from the underlying materials themselves.

The easiest way to understand the intricacies and varieties of textures can be seen within a single tree.Thebark, flowers, leaves and branchesthemselves often feel different to the touch, and they have a dramatic impact on the textural effect of a space when viewed from afar.

Texture is something many beginnersignore, or only consider at a micro level – for a specificplantormaterialtype.Professional designers recognise particular use and emphasis of textureacrossa site can dramatically enhance the users experience in a space.

Plants and materials withfine texturestend torecedeinto the background, lengthening a space and making it harder to perceive specific components at first glance.This can help bring other similar components within a space together – forming a nice consistent background.

The opposite of this happens when you choose plants or materials withcoarse textures.Theyadvancein the space, drawing your eye.Light often ‘catches' on the rough, spiky or scratched façade, creating an interesting interplay between areas of light and shadow.

A roughly textured material or plant can make a space feelsmallerif they are spread across a space – like the inside of a log cabin.They can stand out as a feature item orfocal pointif isolated – especially against a finely textured background.

Finally, texture also serves afunctional purpose.Placing roughly textured materials in areas people mayslip– such as around pools or on steps – adds a level of safety.Alternatively, placing sharp or rough textures in areas around pets or children mightnotbe a great idea.

Thinking about the texture of your material and plant choices in this way helps you determine whatfinish choicesyou should make in certain circumstances – toaddorremove coarse or fine textures.

Similar to colour, once you have a layout of spaces you are happy with, it can be useful to create a sort of‘texture' map.Think about whether you want a space to appear larger or smaller, or have certain features in place.

4.华体会ufcThe Three Aspects Of Proportion In Garden Design

Proportion is another element, like line, colour and texture, that falls under ‘form华体会平台赞助‘ in landscape design theory.It's concerned with the physical properties of an object or overall space.

It covers a few aspects of landscape design –a components proportional dimensions (it's height, length and width), a components sizerelativeto things around it in the garden, and a component's sizecompared to the users– if it's "human scaled".

A common way to make something feel like it's the right size is to followthe rule of ‘thirds'.Take your longest dimension for a component, and make the others1/3 or 2/3 that measurement.It won't always work, but is a good way to start planning dimensions for paths, lawns, garden beds and other outdoor spaces.

This also works well for the height of components – even trees, although that is more about the potential range of the mature height of a tree, rather than an exact height.

Once you've adequately proportioned an individual component, it's helpful tocompare it to the rest of the components around it in a space.You can change the feel of a space not just by adjusting it's dimensions, but by playing with the items within the space – and their relative proportions to each other.

Good landscape designers use proportion between components in their designs toemphasisesomething they want tohighlightor tominimisesomething they want tohide.Small plants beneath a feature plant, or larger plants around a utility box are good examples of this use of relative proportion.

A good example we've all seen is how the moon looks larger closer to thehorizonthan in the sky.Despite not changing size during it's journey through the night, it looks visibly larger the closer it is to the horizon.

华体会ufcThat said, the very best garden designers recognise, like many landscape principles outlined here, that sometimes the best results come frombreaking the rules.

Such as taking advantage of a beautiful oversized tree by purposefully reducing the size of things around it, or allow it to otherwise ‘dominate‘ the space – like the Oak tree in Christine Ten Eyck's garden further down the page.This way, you are working with your surroundings rather than attempting to tame them.

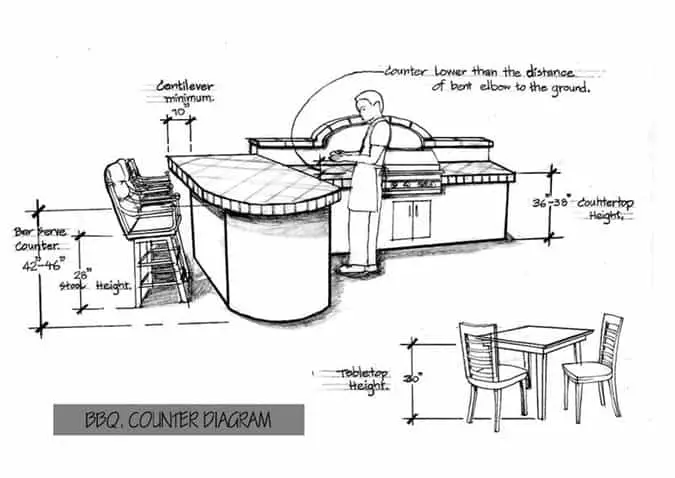

The final thing to think about when it comes to proportion in landscape design is to have everything you can scaled to "human size".This means as you sketch out ideas, layouts and designs, draw things to scale (no pun intended) and determinewhat that would be like inreallife– at 1:1.

Make sure the paths, walls, steps, decks, fences, plants, rocks and all the various materials and surfaces you design matchhow you want to use and enjoy them.Don't have steps or benchestoo highto use properly.Don't make your pathstoo narrowso they're basically unusable.

The best way to test this is to measure out your design in your house or garden and see if it works.Another way is to, from the start, stick to ‘standard‘ measurements of heights, widths and lengths.Measureexisting things around youand use those to start your designs.

As I mentioned above, proportion is more about how large or small something is relative to it's surroundings.How large will yourmature trees or plants becompared to things around them – including your house?You may find as you design that your path works well at a width of 1.5 m (~5 ft) but then see it is far too wide for the surrounding design.

So when you work through your design, follow therule of thirdsto help determine the dimensions of components.Pay attention toproportion between componentsto emphasise or minimise them.And always think about making things"human scaled"so they allow you to do what you want to do.

5.Create Interest In Your Garden By Using Contrast

Unlike the elements outlined above, contrast is not really something on it's own.It takestwo competing versions of an element– straight vs curved lines, dark vs light colours, bold vs soft shapes – andthrough this opposition adds to a style or overall effect within a space.

This competition of elements doesn't need to occur within the same space or material – it can happen in different ways across your design.

For beginners, it's best to start with obvious contrasts.So have a garden bed withsofterplantings like grasses or ferns, and add a ‘sharp' orboldcomponent within or next to it.It could be another plant with a strong visual outline, or a sculpture or even a deciduous feature.

You could make the tree extra-interesting if it has small, soft leaves instead of the bold shapes above.This means it can ‘blend' into the garden bed during spring and summer, and after the leaves fall in autumn, the branches become a strong, shapely element – contrasting the plants in the garden bed.

This change in role fromone season to anotheris what separates landscape design from other design disciplines.

As you explore ideas in your design,look for opportunities to add contrast within a space.If you have too much of something – similar shapes, finishes, colours etc.– it can create a monotonous feeling.Unless this is explicitly what you want, try to add a material, colour or shape that provides some contrast.

Another, more subtle way to introduce contrast is totake existing materials or plants within the design and change one aspect of it.For example, you might want a paving area that has a particular colour and finish of stone.What happens if you change the finish of some them?Make a row, or a random assortment, smoother or rougher in finish?

You can try a similar thing with bricks.Many houses have sporadic bricks of a different colour – why not add that into a paved brick area?Again, for plants, maybe you have a border or garden bed of purple lavender, and every so often you add a white variety?

One of the best ways to introduce contrast into a material or particular area is to ‘borrow‘ an element from another space.Match your rough paving finish to a similar timber or stone finish elsewhere.Or the white lavender links back to the white plants or colours in another area.

This simple approach helpsnarrow your contrasting choices, and has the added benefit oftying different spaces across your yard together.

6.Solid & Void In The Garden – What It Is & How To Use It

Solidrefers to how much somethingphysically or visually occupies space, andVoid is all the empty space around it.It sounds like a rather basic thing to consider a principle, but it is a common concept across many design disciplines.

Other terms that fall within this concept are ‘Positive vs Negative‘ space, or perhaps referring to the ‘Weight‘ of an object within a space.In simple terms, it's reflectinghow one component, or part of a design, impacts yourperceptionof that area.

The simplest example is to look at a large tree in a garden.The size of the tree has a big impact on the ‘weight' of the space, and it's shape even more so.

The example above shows the ‘Solid' imposing Oak tree in the middle of the space.To balance this solid with Void, the designer cleverly kept many of the garden beds and spaces around it at ground level.

Solid vs Void manifests itself differently in different industries.In graphic or web design, it's about the importance ofwhiteornegative spacecompared to the content – text or imagery.

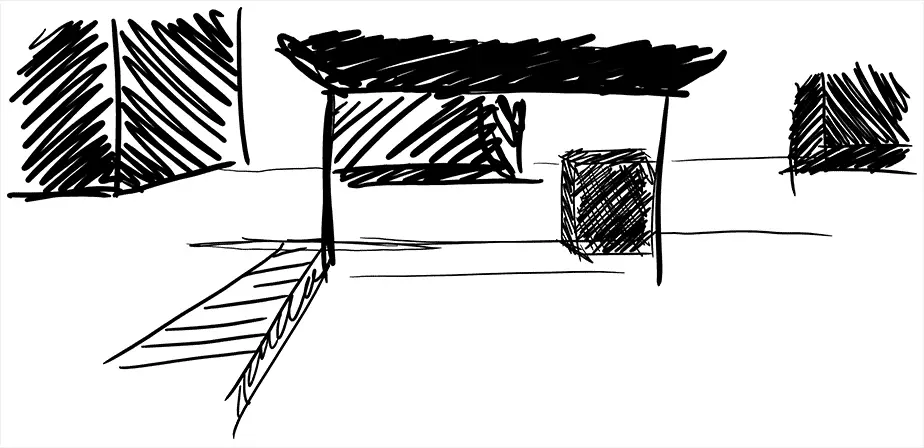

In architecture it is literally how a room isshaped.We occupy the void, while the walls, floor and ceiling are the solid.The important thing in architectural theory is that the solid doesn't have to be literal – it can be ‘implied'.The way a cantilevered roof implicitly suggests walls around it is a good example.

As a landscape design principle, it follows a similar pattern.Solid refers to the physical within an area, while space is the… space.

华体会ufcThis principle works across all scales within a garden design.Below, the brick path is the void compared the fill of the surrounding garden beds.

As we saw above, a larger tree surrounded by a low garden imitates the solid vs void scenario.So how do you go about designing with this notion of solid and void in mind?

The best way is todraw scaled plans, sections and perspective drawings(easier to do if you trace over a photo of the space).Then explore howchanging one component(a tree, wall, patio etc.) within the design impacts how you would view or move through the space.

Start with a base you want to draw over – like your original design sketch – or section or even a photo of the space.Add another layer of trace (or non-waxed baking paper) over the top.Then, redraw this particular component, making itlarger, changing theshapeorlayoutor even it'sposition within the space.

If you don't want to sketch out the actual object, simply ‘block' it – using a black rectangle or other shape to "suggest" or intimate the item.It won't necessarily be pretty but it can be effective.

Do this as many times as you like, seeing what it will look like in plan, side on or in perspective.Don't forget toresearch and draw the mature size of plants and treesso you are properly representing how the space will look when they grow to full size.

Stepping back from the how for second, we can consider broader design approaches that deal with solid and void.A great example is the idea of"open enclosed spaces".

That sounds like an oxymoron, but in reality refers to spaces likepatiosandterracesthat are sheltered overhead, but not walled in on all sides.The solid weight above provides a sense of comfort and protection, while the expansive view out still allows you to view what's happening around you.

One final thing to note is although we've discussed physical objects and space comprising solid and void, you can also consider the effect ofshadow and light.Shade is dark, and recedes in the landscape, changing it's character.Light is bright and advances, highlighting points, and helps carve up space in otherwise empty areas.

7.华体会ufcRepetition & Rhythm Creating Dynamic Garden Designs

Repetition is what it sounds like – repeating something within a design.It could becolours, materials, a particular motif, a layout or a specific component like plants or steps.Seeing the same things repeated unconsciouslybuilds familiarity with the space, calming visitors and users of the space.

You don't need to be overt with repetition either – have everything exactly the same across a design.Sometimes repetition is more about an ‘echo‘ to another area.As we've discussed, it could berepeating a material, colour or finish in multiple places.

One way to try to design with this is to take something in your design,scale it up or down, and place these versions elsewhere in your garden.A feature tree in one spot can have little ‘echo' shrubs or grasses in other spots that ‘call' back to it.

Despite the importance of repetition,too much can make a design drab and stale.A hospital or school corridor can certainly be repetitive, and they're generally not places people enjoy walking through time after time.

So if your design, unless it happens to be extremely formal or modern, starts to feel the same, it's worthadding somerandomnessinto it in some way to liven things up.And a good way to inject some is to have less repetition and focus more on ‘rhythm'.

Rhythm refers to thepacing of a design.So when you are moving through a space, how does itfeel?Do things come across your vision haphazardly, or is there aflow?Do you get a sense of familiarity from the materials, colours and other components?Or is there something new at each turn?

This applies more to larger gardens, but you can imitate these sensations even in smaller ones.As you design, determine the main ‘viewpoints‘ in your design.

What direction will the user be looking out towards?What components will you place there, and do they seem related?Or from different gardens?

Once you have these planned out,experiment with direct and indirect ways to access these spaces, and see how you can add rhythm or repetition to enhance that journey.

8.Reduce Options & Bring Unity To Your Garden

Like contrast, unity is more abouta collection of principles or elementsand not something you can ‘apply' on it's own.It is, however a kind of marker – something you should aim for – and always consider as you are designing any outdoor area.

In many ways Unity is all aboutlimitinghow many of each element you opt for in your design.Like I said earlier,limiting your options to a few key colours, or textures or line styles can really help you as you design.

I've mentioned it before, but a great way to simplify things is tostart designing with a specific garden stylein mind.Look at images of styles you like and see what colours, plants and materials they are using.Take that inspiration, scatter it across the different areas in your garden, and you'll find it hardnotto have unity in your design.

Bringing a garden together tends to be one of those things you only think about when you find examples of where itdoesn'thappen.You'll notice is that plants, components and ornamentsscattered around randomlydoesn'treallywork.

This is a common mistake people make in their actual gardens because they are focused onone specific item, area or project.This leads to a lot ofsiloed, isolated things that don't relate to anything else around them.

Another way to try and introduce unity into your design is to sketch things out multiple times and move things around – objects, materials and colour – to see how things change.

The best way to remedy this is toremove things one at a time.See what reallyaddsto the space vs whatdetractsfrom it.The saying "less is more" is often true.

When it comes to positioning the solid, physical components in any space, a good rule of thumb is to place them inodd numbers.This works especially well with plantings.Place them in threes, fives etc.– even if they are different species and sizes.It looks more natural to our eye to have things kind of ‘clumped' together in odd sets, not even.

Start with your main ‘feature' element– like a large tree –and work out from that position.Because it is the focal point, you want it to contrast a little with its surroundings.Use whatever makes it ‘pop' – shape, colour, size etc.–as little as possiblein the backgroundaround it.

Finally, as with any principle, you can, if you are daring, try to reject it.One way to reject the kind of manicured unity we have been talking about is to do the opposite – make things lessobvious, repetitive or consistent.

A good example iskeeping some areas purposefullywild, without clear lines of sight or a focal point.These spaces work better if you're ‘unsure' within them – not from outside looking at them.

A small bamboo forest is an excellent example, where the lack of focal point fosters a sense of enclosure and protection.

9.Harnessing Hierarchy When Designing Your Garden

A very visual principle.Essentially,what you see first, what catches your eye.After the first impression,what does your eye flow to next?Andthe next thing?Finally, what is thebackgroundbehind all of this?

Most people know of this as the‘focal point'.In many cases it's aspecific component, placed withintent, tocapture attentionandstand out.Hierarchy as a principle goes a step further, where you consider notjustthe main focal point, but the components around it that contribute to the whole effect.

华体会平台赞助Each of the elements that underpin ‘form' in landscape design theory contribute to this sense of hierarchy.You can useany one of line, colour, texture or proportionto bringone component in a spaceforward, or push others to thebackground.And contrast can exacerbate this layering even further, again, applying it to any of those elements.

Hierarchy also happens at multiple scales.

It can be within aspecific garden bed– the layout and selection of plants, where one ‘pops' from the others.

It can be withinan area or ‘room' in a design– with a specific feature standing out due to height, material, shape or other factors.

Finally you can make a华体会ufcspecific component or space within your whole garden designthe main focal point.The thing from which all other aspects of the design either link to, or contrast with.

The best designers are able to ‘invert‘ hierarchy – specifically a focal point.Perhaps the feature you want to ‘highlight' as a focal point is not anything within your design at all.

It could be the space frames a particular external view.Orencourages you to listen to your surroundings.Or is simply a place toenjoy the sun, the breeze, or even the shade.Designs like this recognise that landscape designs can be more than pretty visuals.

10.华体会ufcThe Elegance of Symmetry & Energy of Asymmetry In Garden Design

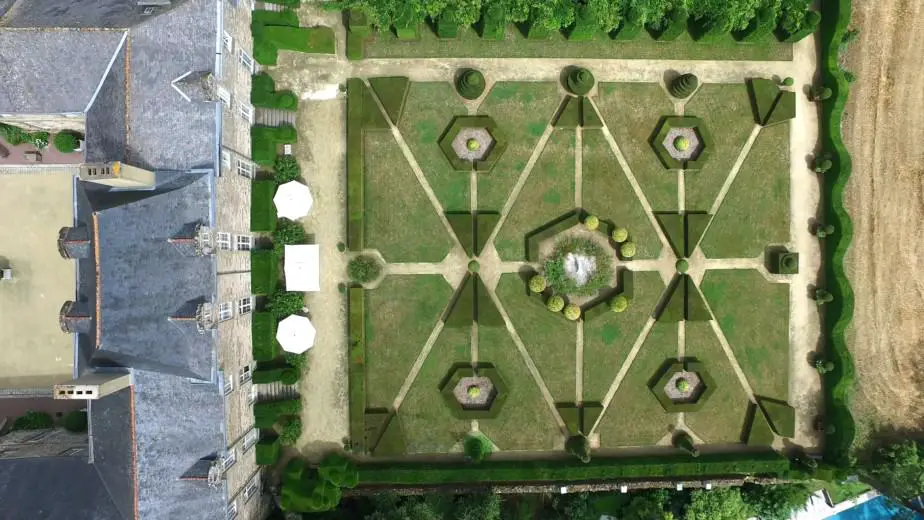

Symmetry, like line, can quickly tell you whatstyleof garden you are looking at.Formal gardens lean into symmetrical layouts, whileinformal gardens opt for asymmetry– spreading ‘weight' of spaces around more naturally.

Symmetry is easier to develop at first glance, but requires a keen eye fordetailandexacting standards.Somethingslightlyoffline or out of place is instantly noticeable.Like modernist design,simplifying things tends to lead to less places to ‘hide' mistakes.

Asymmetry is appealing if you can do itright.As we talked about weight above, you need to understand howheavythe components in your space feel.

The best way to create an asymmetrical design is to test your design and layout of components.The simplest way is through drawing sketches, sections/elevations or even making simple ‘working models'.

As you explore positioning things, you need to know the approximatemature sizesof the plants and trees you are placing.You want to understand the space when it is ‘complete‘ – not when it's first planted.

Once you have an idea of those heights and shapes, you can quickly sketch out a view, changing how things are positioned to see what you feel works best.

This approach works well if you have a particular position in your design you want toview this space from– it could even be in the house!Lastly, ensure any sketch or section you draw has anoutline off a human figurein them – so you can understand how large or small different spaces are.

华体会ufcAnd this covers the 10 Most Important Principles in Landscape Design Principles you can refer to as you develop your own garden designs.Let me know what you chose to work with in your landscape design process down below!